Invasive Species

The Belle Isle Aquarium website has numerous resources about invasive species. In addition to teacher's lesson plans obtainable by clicking on the adjacent button (or on this link: http://detroitaquarium.weebly.com/lesson-plan-ideas.html), in depth information, activities, and games that educate about invasive species can be accessed at the following link: detroitaquarium.weebly.com/educating-about-invasive-species.html

What are invasive species?

An "invasive species" is a plant or animal that is non-native (or alien) to an ecosystem, and whose introduction is likely to cause economic, human health, or environmental damage in that ecosystem. Once established, it is extremely difficult to control their spread

During the past two centuries, invasive species have significantly changed the Great Lakes ecosystem. In turn, the changes have had broad economic and social effects on people that rely on the system for food, water, and recreation.

The Belle Isle Aquarium website has numerous resources about invasive species. In addition to teacher's lesson plans obtainable by clicking on the adjacent button (or on this link: http://detroitaquarium.weebly.com/lesson-plan-ideas.html), in depth information, activities, and games that educate about invasive species can be accessed at the following link: detroitaquarium.weebly.com/educating-about-invasive-species.html

What are invasive species?

An "invasive species" is a plant or animal that is non-native (or alien) to an ecosystem, and whose introduction is likely to cause economic, human health, or environmental damage in that ecosystem. Once established, it is extremely difficult to control their spread

During the past two centuries, invasive species have significantly changed the Great Lakes ecosystem. In turn, the changes have had broad economic and social effects on people that rely on the system for food, water, and recreation.

Invasive Animal Species

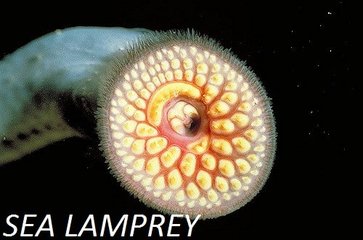

At least 25 non-native species of fish have entered the Great Lakes since the 1800s, including round goby, sea lamprey, Eurasian ruffe, alewife and others. These fish have had significant impacts on the Great Lakes food web by competing with native fish for food and habitat. Invasive animals have also been responsible for increased degradation of coastal wetlands, resulting in loss of plant cover and diversity.

At least 25 non-native species of fish have entered the Great Lakes since the 1800s, including round goby, sea lamprey, Eurasian ruffe, alewife and others. These fish have had significant impacts on the Great Lakes food web by competing with native fish for food and habitat. Invasive animals have also been responsible for increased degradation of coastal wetlands, resulting in loss of plant cover and diversity.

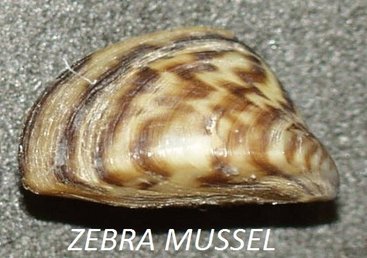

Non-native mussels and mollusks have also caused turmoil in the food chain. In 1988, zebra mussels were inadvertently introduced to Lake St. Clair, and quickly spread throughout the Great Lakes and into many inland lakes, rivers, and canals. Since then, they have caused severe problems at power plants and municipal water supplies, clogging intake screens, pipes, and cooling systems. They have also nearly eliminated the native clam population in the ecosystem.

The spiny water flea (Cercopagis pengoi) is another species that recently entered the Great Lakes. This organism, a native of Middle Eastern seas, is a tiny predatory crustacean that can reproduce both sexually and, more commonly, parthenogenically (without fertilization). This allowed them to quickly populate many areas in the Great Lakes.

Invasive Plants

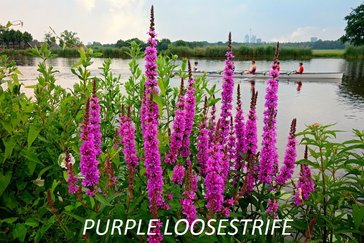

The Great Lakes have also been troubled by fast-growing invasive plants such as common reed (phragmites australis), reed canary grass (phalaris arundinacea), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), curly pondweed (potamogeton crispus), Eurasian milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae), and two types of non-native cattails (Typha angustifolia and Typha glauca). Some of these plants are prolific seed producers, which allows them to spread rapidly over large areas. Invasive purple loosestrife, for example , are 2-3 meters tall and can produce 2.7 million seeds each year. Others reproduce from fragments of root or rhizome, which hinders removal and control. All have become established quickly in the Great Lakes, displacing the native plant populations that support wildlife habitat and prevent erosion. Their prevalence in recreational waters also hinders swimming and boating.

The Great Lakes have also been troubled by fast-growing invasive plants such as common reed (phragmites australis), reed canary grass (phalaris arundinacea), purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria), curly pondweed (potamogeton crispus), Eurasian milfoil (Myriophyllum spicatum), frogbit (Hydrocharis morsus-ranae), and two types of non-native cattails (Typha angustifolia and Typha glauca). Some of these plants are prolific seed producers, which allows them to spread rapidly over large areas. Invasive purple loosestrife, for example , are 2-3 meters tall and can produce 2.7 million seeds each year. Others reproduce from fragments of root or rhizome, which hinders removal and control. All have become established quickly in the Great Lakes, displacing the native plant populations that support wildlife habitat and prevent erosion. Their prevalence in recreational waters also hinders swimming and boating.

In the St. Lawrence River, studies have found that disturbances by boat or fish may facilitate the spread of common reed, a very persistent invasive plant. Dense beds of common reed may threaten local fish and bird habitats.

What EPA and Other Agencies are Doing

To prevent and control additional invasions in the Great Lakes, coordinated efforts are under way by U.S. and Canadian governments, eight state governments, two provincial governments, and regional and local programs.

What EPA and Other Agencies are Doing

To prevent and control additional invasions in the Great Lakes, coordinated efforts are under way by U.S. and Canadian governments, eight state governments, two provincial governments, and regional and local programs.

Ballast Water Regulation

Ballast water is taken onto or discharged from a ship as it loads or unloads its cargo, to accommodate changes in its weight. Thirty percent of invasive species have been introduced in the Great Lakes through ballast water. In the early 1990's, the U.S. Coast Guard began requiring ships to exchange their ballast water, or seal their ballast tanks for the duration of their stay. The Coastal Guard later used their success in the Great Lakes to develop a ballast management program for the entire nation. Currently, the Coast Guard is in the process of developing ballast water discharge standards.

Ballast water is taken onto or discharged from a ship as it loads or unloads its cargo, to accommodate changes in its weight. Thirty percent of invasive species have been introduced in the Great Lakes through ballast water. In the early 1990's, the U.S. Coast Guard began requiring ships to exchange their ballast water, or seal their ballast tanks for the duration of their stay. The Coastal Guard later used their success in the Great Lakes to develop a ballast management program for the entire nation. Currently, the Coast Guard is in the process of developing ballast water discharge standards.

Preventing Potential Invaders

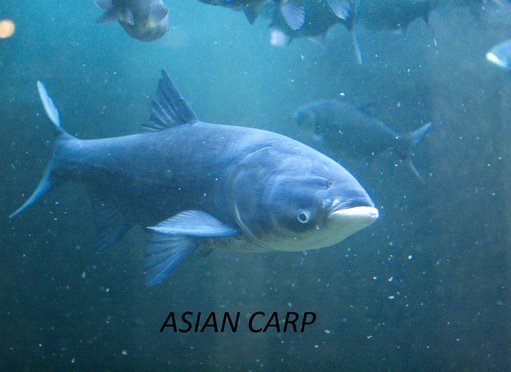

Based on the problems caused by non-native species, scientists are also closely watching other species that have invaded nearby ecosystems. Asian carp are of particular concern because they have been found in nearby waterways that eventually connect to the Great Lakes. In 2004, EPA and other state and local agencies began construction of a permanent electric barrier to prevent the fish from entering Lake Michigan (more about the barrier).

EPA is also studying how existing invasive species have become established in the Great Lakes. These studies will help develop new techniques to predict future invasions.

Based on the problems caused by non-native species, scientists are also closely watching other species that have invaded nearby ecosystems. Asian carp are of particular concern because they have been found in nearby waterways that eventually connect to the Great Lakes. In 2004, EPA and other state and local agencies began construction of a permanent electric barrier to prevent the fish from entering Lake Michigan (more about the barrier).

EPA is also studying how existing invasive species have become established in the Great Lakes. These studies will help develop new techniques to predict future invasions.

Next is Sea Lamprey